- Home

- Jessica Alexander

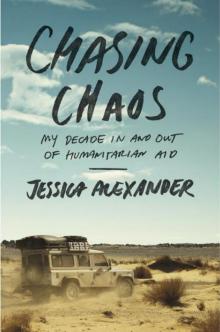

Chasing Chaos: My Decade In and Out of Humanitarian Aid

Chasing Chaos: My Decade In and Out of Humanitarian Aid Read online

More Praise for Chasing Chaos

“A fresh, very readable, highly personal account of the trials and tribulations of a young aid worker as she confronts the daily realities—the good, the bad, and the very uncomfortable—of life dealing with some of the most important humanitarian challenges of the last decade.”

—Ross Mountain, Former United Nations Deputy

Special Representative of the Secretary General and

Humanitarian Coordinator

“Not only is Jessica Alexander a wonderful writer—her clear, evocative prose transported me into refugee camps in Darfur, war trials in Sierra Leone, and post-earthquake Haiti—but she is honest about the complexity of ‘doing good,’ without being defeatist. Funny, touching, and impossible to put down, this book should be required reading for anyone contemplating a career in aid, and for all of us who wonder how we can make a useful contribution to a better world, wherever we are.”

—Marianne Elliott, author of Zen Under Fire:

How I Found Peace in the Midst of War

“You’ll start Chasing Chaos because you are interested in humanitarian aid. You’ll finish because of Jessica Alexander’s irresistible storytelling: her honesty, her humanity, her wackadoodle colleagues, her dad. I loved it.”

—Kenneth Cain, author of Emergency Sex (and Other

Desperate Measures): True Stories from a War Zone

“A no-holds-barred description of what it is like to travel to world disaster sites and engage in the complex, challenging, nitty-gritty work of making a difference across lines of culture, class, age, gender, and perspective. In telling the story of her decade as a young and passionate humanitarian aid worker, Jessica Alexander also manages to tell us the best and the worst of what this work is like and to speculate on the aid establishment—how it has changed, where it works, and what its limits are. A must read for anyone with global interests—and that should be all of us.”

—Ruth Messinger, president, American Jewish World Service

“Chasing Chaos examines the lives that aid workers lead and the work [that] aid workers do with honesty, clarity, and warmth. While the book is peppered with hilarious anecdotes—it is also salted with tears. Honest, genuine, heartfelt tears. This life and this work that aid and development workers embark upon so often oscillates wildly between stomach-bursting laughter and shoulder-seizing weeping—Chasing Chaos captures these oscillations, and the doldrums in between the ends of the spectrum, perfectly.”

—Casey Kuhlman, New York Times bestselling author of Shooter

“The compelling quality of Chasing Chaos is Alexander’s honesty, sharp observations, and conversational prose. With humor and insight, she shares the intimate details of her everyday life. Even if you’re a seasoned traveler, this entry into the world of humanitarian aid organizations—the good, the bad, and the frustrating—is fascinating.”

—Rita Golden Gelman, author of Tales of a Female Nomad

“A hardened idealist’s challenging look at the contradictions, complications, and enduring importance of humanitarian aid.”

—Robert Calderisi, author of The Trouble with Africa: Why Foreign Aid Isn’t Working

“In Chasing Chaos, Alexander takes us to a place where few outsiders can go, cracking open the rarefied world of humanitarianism to bare its contradictions—and her own—with boldness and humor. The result is an immensely valuable field guide to the mind of that uniquely powerful and vulnerable of beasts: the international aid worker.”

—Jonathan M. Katz, author of The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster

Copyright © 2013 by Jessica Alexander

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Broadway Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC., New York, a Penguin Random House Company.

www.crownpublishing.com

BROADWAY BOOKS and its logo, B D W Y are trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Alexander, Jessica.

Chasing chaos : my decade in and out of humanitarian aid /

Jessica Alexander. — First edition.

pages cm

1. Humanitarian assistance—Sudan—Darfur. 2. Sudan—History—Darfur Conflict, 2003- I. Title.

HV555.S73A44 2013

361.2′5092—dc23

[B] 2013008182

ISBN 978-0-7704-3691-9

eBook ISBN: 978-0-7704-3692-6

Maps by David Lindroth, Inc.

Cover design by Maayan Pearl

Cover photographs by Kurt Drubbel (desert); © Ben Walsh/Corbis (car)

v3.1

TO DAD

and

TO MOM, who is with me wherever I go

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

All Skin and Grief

NORTH DARFUR, 2005

Hot Pockets and Sunny D

NEW YORK CITY, 2000

People Died This Way

RWANDA, 2003

Does Everyone You Work With Have Dreadlocks?

NEW YORK CITY, 2003

Zulu X-Ray India 9

WEST DARFUR, 2005

Center for Survivors of Torture Fancy Dress Night

NORTH DARFUR, 2005

More Money, More Problems

SRI LANKA AND INDONESIA, 2005

I Make a Living Off the Suffering of Strangers

NEW YORK CITY, 2006

War Don Don, Peace Don Cam

SIERRA LEONE, 2006–2007

Saving Lives One Keystroke at a Time

NEW YORK CITY, 2008–2009

I’m Headed to Haiti, Where Are You Going?

HAITI, 2010

Epilogue

2013

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

About the Author

All Skin and Grief

NORTH DARFUR, 2005

I awoke as I did every morning. The call to prayer erupted at 5:30 a.m. and was so loud I could have sworn the muezzin set his amplifier right next to my pillow. But the scratchy voice that shrilled through the old speaker came from the roof of the adjacent mosque.

Someone make him stop. Please, just make it stop.

When the muezzin paused to take a breath, a chorus of chickens, goats, and a baby crying in a house nearby filled the momentary hush. I peeled the mildewed towel from my face—the one I had drenched with water and placed on my forehead before bed. It was the only way I could fall asleep in the smothering Darfur heat. Every evening I’d dunk my pajamas in water and lie on the foam mattress, eyes shut tightly, reveling in the cool wetness clinging to my skin, hoping I would fall asleep before it evaporated into the dry night. But that almost never happened.

As the muezzin continued, I got out of bed listlessly; I had to get to the camp early that day. Close to one hundred and twenty thousand displaced people lived in camps around the city of El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur; twenty-four thousand of them lived in the camp where I worked, Al Salam. Families would be sitting outside the registration tent this morning, already lined up and waiting for the camp processing to resume. Since the other two camps—Abu Shouk and Zam Zam—were at full capacity, we had to make room for the new arrivals. We registered, screened, and distributed food to the weary families as quickly as possible, but each day an endless flow of colored specks in the sandy distance moved closer to the camp: men and women carrying babies in their arms and bundles on their heads, donkeys trudgi

ng slowly by their side. It was a war. People kept coming.

I went to the small bathroom in our compound, thinking that maybe, miraculously, the water would work. I turned the small faucet, hoping for a trickle, but it coughed and sputtered. My calves and armpits hadn’t seen a razor for weeks. My hair hung in oily clumps around my face and smelled like dirty dishwater. I pressed the lever to flush the toilet, but it went limp beneath my fingers. The day before we’d accidentally left the lid open and bugs had swarmed around the seat. Today the lid was down but it still smelled like rotting shit.

I brushed my teeth with the bottled water we had on reserve. Lila, my Kenyan colleague who lived with me, walked into the bathroom and saw me, water bottle in hand. “Still?” she asked. She was wrapped in a bright pink sarong, holding soap and shampoo, hoping to take a shower.

“Still,” I said through a mouthful of toothpaste.

The water problem was supposed to be fixed days ago, but as with everything in Darfur, we waited.

“Adam, mafi moya,” I had said some days before. (“there is no water.”) Adam, our Sudanese colleague, was responsible for maintaining the guesthouses where we lived. “When is the pump going to be fixed?”

“Hello, Testicle.” Adam couldn’t pronounce my name—Jessica—so it always sounded as if he were calling me a testicle. “Water will be there today!”

“Adam, you said that yesterday and the day before and we still have no water.” I was so tired and defeated that the words came out flat and quiet.

“I know. Tonight, inshallah!”

Inshallah—God willing—qualified most Sudanese commitments. “Inshallah, I’ll be there.” “It will be finished by the end of the week, inshallah.” “Your visa will come tomorrow, inshallah.” If God willed these things to happen, they would. In my experience, God tended to be unwilling.

Dressing in my baggy, worn-out khakis and long-sleeved shirt, I didn’t need a mirror to see how awful I looked. With a layer of sweat and dirt already covering my face, my skin couldn’t absorb the SPF 55 sunblock smeared on it, so I walked into the unrelenting sunshine with a filmy white clown mask.

As it did every morning, breakfast consisted of a hard-boiled egg and a cup of Nescafé. Lila was already sitting inside the small kitchen. It had been ransacked. Canned goods were scattered everywhere and the floor was sprinkled with flour and rice; their ripped burlap bags slunk low. “Are you kidding me? Again?” I said. “Those goddamned cats.”

Street cats roamed our compound, keeping away the hedgehogs who scurried through North Darfur like squirrels in Central Park. Before Darfur I had never seen a hedgehog; they looked like miniature porcupines. Some people thought they were cute; to me they were prickly nuisances, leaving stinky turds under our beds and in the back of our closets. But the cats were worse. We locked the door to the kitchen every night, but they managed to slink under the small crack at the bottom.

Lila crouched down to sweep the mess. I grabbed a match and went to light the stove to boil water for our eggs and coffee. It wouldn’t take. I tried again but only a rapid tick-tick-ticking came from the stovetop. Lila sighed, “I told Adam last week that we were running low on fuel.”

“Can you remind me what he gets paid to do around here?” I asked, still flicking the stove, the anger rising in my throat.

Lila looked up and shrugged with the same resignation we all embraced to survive the lack of control over our most basic needs.

Having lived in Darfur for close to seven months, I felt at turns dizzy, tired, and depressed. A low-level rage had been slowly building for weeks. I had seen people’s burnouts turn them nasty and cynical. But really I just wanted some water. To get the rank smell of my own body out of my nose. My sanity relied on so few things here—water and fuel being the primary ones. It felt as if even these were too much to ask for.

But it wasn’t only the loneliness or the living conditions; it was the unrelenting feeling of futility within the enormity of this war. The work my colleagues and I were doing for international humanitarian agencies wasn’t ending the country’s real problems: the merciless horror of fire, rape, and murder that rode in on horseback. All we could do was provide a few flimsy plastic sheets, rice, and oil to fleeing farmers and their families, some who had walked two weeks to get here. Some came from Chad, some from the Nuba Mountains to our east, others from one of the many small, nameless villages scattered across the dusty Darfur canvas. There was an endlessness to the crisis, and I was exhausted.

It was 2005 and the Darfur crisis had already displaced nearly two million people and claimed the lives of another seventy thousand. People were terrorized off their land by the Janjaweed, the government-backed militias who set fire to farming communities, landing their residents in displaced persons camps throughout Darfur.

“SALAM ALAIKUM,” I said to Yusuf, the guard who lay outside the door to our compound. He slept there each night, supposedly protecting us. It was like plopping Grandpa on a rocker in front of our door. If there weren’t teenagers with AK-47s kidnapping and murdering people, it would have been a funny joke.

“Alaikum Salam. Keif Elhaal?” he asked cheerfully, standing up—how are you?

If I had known the Arabic to say, I haven’t bathed in a week, haven’t eaten in a day, my fatigue has reached hallucinatory levels, and it’s 6:30 a.m. and I’m headed to the camp where I’m pretty sure I’ll have to face thousands more people and tell them that we don’t have enough supplies for them. So, actually, Yusuf, I’m pretty shitty. How about you? I would have.

But the only response I knew to this question in Arabic was Kulu Tamam—all is good.

Nothing around me was good. Like the horse who was slowly starving next door. Every morning when I passed it tied to the tree outside our neighbor’s compound, I wondered whether the animal, all skin and grief, would be alive when I returned. The family still used it to carry bundles of firewood, sacks of grain, barrels of water—whatever could fit on the rickety cart they strapped to the horse’s back. Its neck drooped low and its spine and rib cage jutted out in sharp relief, loose hide sagging toward the ground.

It was a short walk from the compound where Lila and I lived to the office. Woolly scrub bushes lined the roads; I trudged through the rust-colored earth, kicking up cinnamon sand with each step. Children often teased us expats on our walk to work. Sometimes they’d run up behind us and laugh and giggle screeching “Khawaja! Khawaja!”—white person. Other times they’d sneak up close, touch our hair, and run away. The soldiers who worked for AMIS (African Union Mission in the Sudan) had corrupted some of the boys and it wasn’t uncommon for them to yell “suck my cock” or “big tits” when white women passed. The rowdier ones sometimes even tossed rocks at our backs. But they were gentle tosses, meant to get a rise out of us, testing us to see how we’d react.

This morning, I saw a bunch of them in the distance.

Not today kids.

I walked past them.

They waited until my back was to them and two pebbles hit me—one on my shoulder and the other on my heel.

You little shits. That did not just happen.

I snapped, all the indignities and frustrations of weeks past converging into a bullet rage. My back teeth clamped down so tightly it felt as if they had welded together. Whipping around, I seized a dusty fistful of rocks from the road and cocked my arm. We froze, staring at each other that way; like a Wild West showdown, for what seemed like minutes but was only seconds. I can’t imagine what I must have looked like to them: a crazy white lady—frayed, displaced, and alone on their streets. They turned and scurried down the dirt road, laughing at me, skipping and pushing into each other, turning back to get another look, and running farther and faster away. I tossed the rocks aside, my hands stained brown from the scooped earth.

I need to get the hell out of here.

Hot Pockets and Sunny D

NEW YORK CITY, 2000

By now I’ve heard it all. “You’re like a young Mother Tere

sa,” a family friend—a corporate lawyer, a doctor—will say, cooing over me and telling me what amazing work I do. “You’re just like Angelina Jolie,” they tell me. “The world needs more people like you,” a friend will remark while looking through my pictures.

I am a humanitarian aid worker. I’ve organized food and shelter distributions for tens of thousands of people displaced by conflict. I’ve bargained with stubborn customs officers looking for bribes to get shipments of lifesaving supplies across borders. I’ve managed programs to provide children education opportunities in the aftermath of war. I’ve slept in tents with rats and gone many a hot West African day without bathing. But most of the time I work behind a desk staring at budget lines and spreadsheets cataloguing the number of jerry cans delivered or latrines built. I write a lot of reports and send plenty of dull e-mails. But I’m not a famous actress, I’m no hero and I’m certainly not a saint.

Yet, I can’t blame people who make grand assumptions about the lives of aid workers. When I first started in this career, I was equally unsure about what this life would look like. As an undergrad at the University of Pennsylvania, the only exposure I had to humanitarian aid was a chance encounter with a Peace Corps flyer in the student center. I entered college in 1995, during the Clinton years, when graduates were receiving job offers from multiple banks and international humanitarian crises like Rwanda and Bosnia happened somewhere far, far away.

In college everyone was studying hard to break into more straightforward fields—business, media, law, medicine—and initially I was happy to follow a more typical professional track, knowing that would please my parents, who were both doctors—my father an MD and my mother a PhD—and had similar expectations of me and my two younger brothers. After graduation, I had no idea what I wanted to do. I did some temp work; I babysat on the side; I browsed the LSAT study guides at Barnes and Noble. I even auditioned for the Rockettes. I showed up for the first audition with seven years of childhood tap dancing lessons under my belt, plus a freshly printed resume featuring my college GPA and spring semester internship at NBC Studios. All the other girls were professional dancers. Somehow, I made it to the second round, where I stood shoulder to shoulder with fifty other girls exactly my height and weight doing high kicks and double pirouettes. The stage manager informed me they’d call if I made it to the next audition. They never called.

Chasing Chaos: My Decade In and Out of Humanitarian Aid

Chasing Chaos: My Decade In and Out of Humanitarian Aid